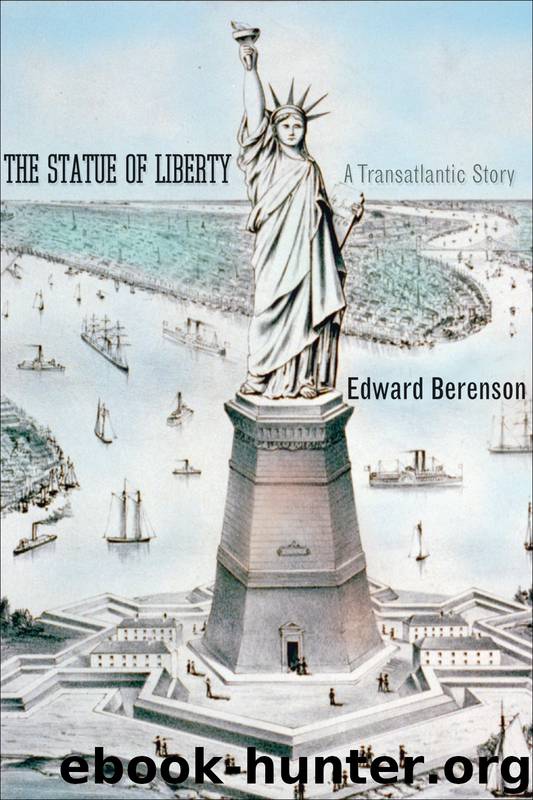

The Statue of Liberty by Edward Berenson

Author:Edward Berenson

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Yale University Press

Published: 2012-09-22T04:00:00+00:00

“Come unto me, ye opprest!” (Literary Digest, July 5, 1919).

Not surprisingly, many of those whose presence had inspired the new law turned against the Statue of Liberty or saw it as unequal to the promise of hope and freedom it was supposed to represent. In 1917 the labor organizer Giuseppe Iannarelli declared, “When the Italians enter this country they see the Statue of Liberty and they breathe freely thinking to themselves that they have at last left the autocratic government and are in the land of the free. Shortly after their arrival they realize their mistake.”30 Carlo Tresca, another left-winger of European origins, echoed these views:

When the ship which transported us to America passed before the historic, colossal Statue of Liberty there was a joyous rush to the side; all eyes were fixed on that torch of light . . . symbolizing the most dear of human aspirations, La Liberta, to see if there was a heart within [the statue] which beat for all of the political refugees, for all of the slaves of capital, for the disinherited of the world. . . . Now I am disillusioned. . . . Perhaps I will pass again, still a pilgrim of the faith, before that statue. Like so many of my comrades—perhaps I will be DEPORTED before these vibrant pages will be read by the Italian workers who suffer, aspire, struggle. Oh, that torch will no longer shine the light it did!31

If such voices lamented the statue’s failure to live up to its ideals—and these constituted the majority of writers disillusioned by the Red Scare and immigration restrictions—some portrayed the statue as symbol of a deep-rooted American evil. The anarchist Luigi Galleani described Lady Liberty as “this monstrous collossus [sic], this republic of the heart of anthracite, with the forehead of ice, with the goiterous throat; this statue of cretinism . . . whose hands are armed with a whip, from whose lips are suspended a knife and a revolver.”32

Not until the 1930s, when the number of newcomers to the United States dropped to almost nothing, did the American public at large come to see the Statue of Liberty as the symbol of immigration and to regard that symbolism in a largely positive light. The politics and policies of the New Deal created the context for this shift in meaning, but it was mostly former immigrants who did the actual cultural work. The Roosevelt administration discouraged the harsh attacks on labor unions characteristic of the previous decade, and since it faced fierce attacks from the right, it tried to soothe tensions between liberals and radicals on the left. But mostly the administration tried to unify a distressed population as much as possible, and that meant fostering more favorable attitudes toward the large number of recent immigrants who now belonged to American society. The journalist Louis Adamic, an immigrant from Slovenia, became central to this effort as he campaigned to persuade teachers to emphasize the important contributions immigrants had made to U.S. history and to present the Statue of Liberty as the symbol of America’s welcome to them.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(13919)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(12964)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(11283)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(11092)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(10937)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(4831)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(4636)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(4620)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(4360)

Paper Towns by Green John(4186)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4049)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4029)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(3924)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(3745)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(3706)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(3638)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(3600)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(3537)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(3471)